JOHN MARTIN

K.L.

(1789-1854)

Mr. Martin's Plans

Artist, Inventor & Engineer. Martin's Grandiose Engineering Schemes for the Metropolis

John Martin: Taking the train to the New Jerusalem? was an article by the Tate's 'John Martin: Apocalypse' exhibition curator and Martin Myrone on 14 November 2011

Myrone commented that:-

Although John Martin is best remembered today as the painter of apocalyptic biblical scenes, by his own account he dedicated something like two-thirds of his time and huge amounts of money to developing increasingly ambitious engineering schemes. From the end of the 1820s until the last few years of his life (he died in 1854), John Martin published a succession of detailed plans and written proposals for transforming London’s sewerage and transport systems. Although his schemes were taken seriously at the highest level, none of them got off the ground in the way Martin envisaged. Rival business interests blocked his plans, and his proposals were sometimes dismissed outright as ‘Babylonish’ visions. His reputation as a painter of wildly imaginative scenery didn't help. In retrospect, Martin’s plans can look as ‘visionary’ as his paintings, as if he was planning to give modern, industrial form to the much-vaunted heavenly ‘New Jerusalem’ which many Britons expected to see rise in their own time. He imagined the embankment of the Thames, something which took place (giving the riverfront its familiar appearance) only after his death.

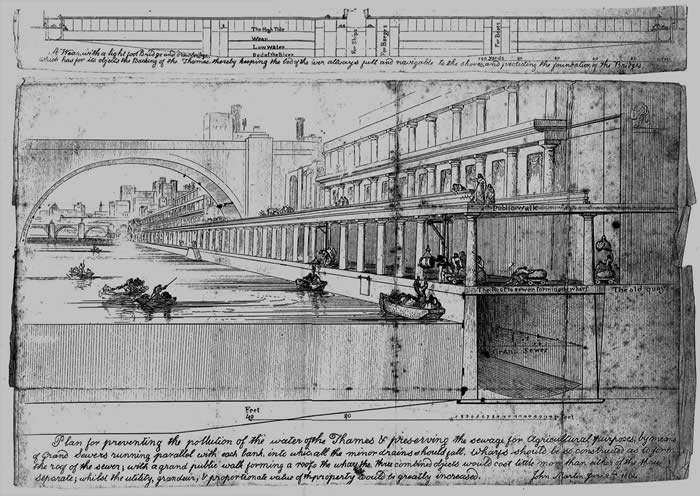

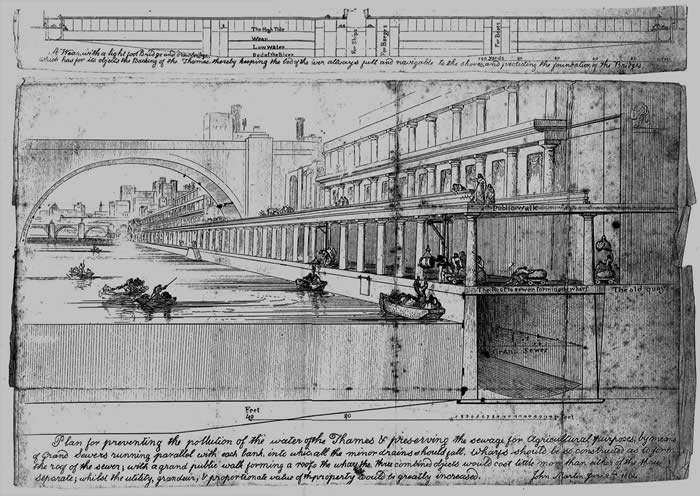

Plan of The Thames Embankment for Sewage Recycling. Lithograph by Martin 2nd June 1834

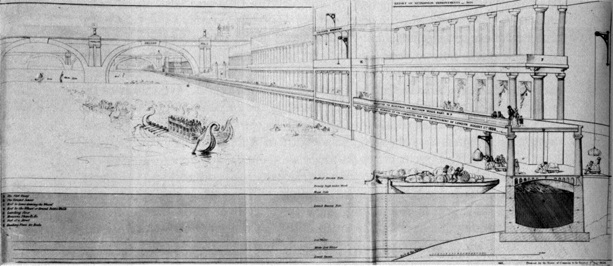

A Later Plan of The Thames Embankment for Sewage Recycling. Note the fanciful Egyptian Galley in the Illustration

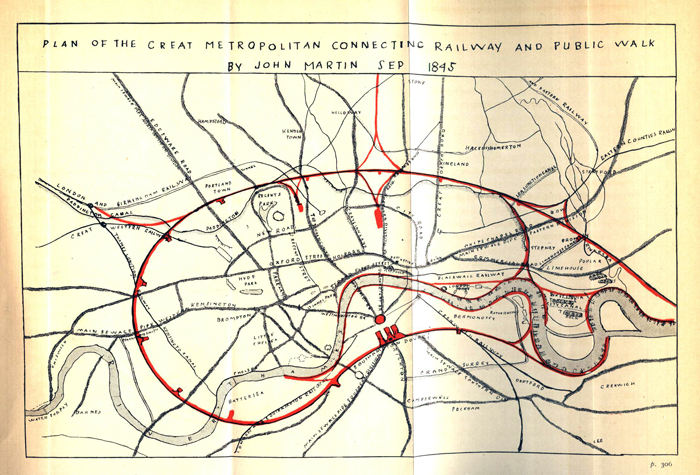

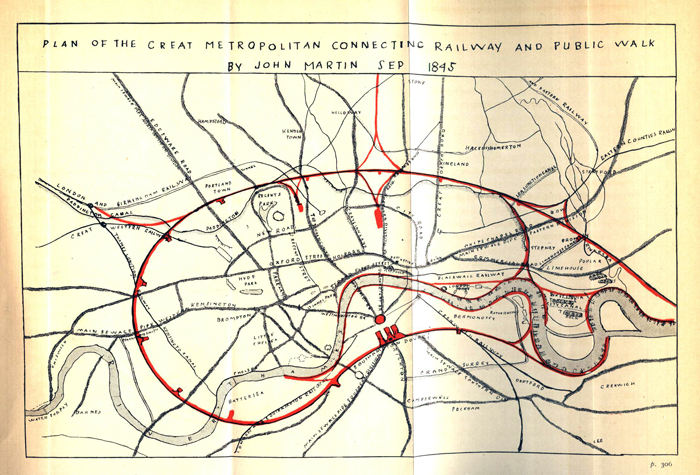

And he proposed a circular railway line, which ran from the east of London, across what was then northerly suburbs (it would have run just north of Regents Park) through the open fields to the west (again, now built-up, central London) and across the south (connecting with Vauxhall), out to Greenwich. As so often with Martin, he felt that his ideas were pilfered by other parties, in this case the Metropolitan Terminii Commission who at the same time as Martin published his proposals came up with their plan for encircling central London with terminal railway stations and barring steam trains from coming into the centre of town

.

Plan of the London Connecting Railway… Engraving by Martin Sept. 1845

As the scholar Lars Kokkonen explores in his essay for the catalogue accompanying John Martin: Apocalypse, the idea that Martin was inspired to come up with these engineering plans from religious feelings doesn't really hold up. He wasn't a religious eccentric or rebellious outsider as is often assumed. The pollution of the Thames and the problems with London’s transport infrastructure were pressing issues in John Martin’s day, and like many others he saw that coming up with proper solutions could be a route to making a fortune. His dedication to civil engineering was another aspect of his commercial outlook. Lars Kokkonen and the print specialist Michael Campbell discovered independently that Martin was an exhibitor at the Great Exhibition in 1851, and I found out that he was able to make some money at the very end of his life from a patent he was granted for ‘Improvements in Apparatus and Means Used in Draining Cities, Towns, and other Inhabited Places and Land’. But at the same time, John Martin seems to have invested far too much in these schemes for this to have been the result of purely rational self-interest. He seems to have been driven by something other than common sense or cynicism, as much with these engineering proposals as with his grandiose and always controversial art. His impoverished background, and lack of education and training may have led him to invest too much (time, money, energy) in enterprises which promised to secure him social prestige, fame and money: he was trying too hard to impress, perhaps?

The satirical magazine 'Punch', in the first half of 1843, proved critical of Martin's ideas:-

METROPOLIS IMPROVEMENTS.

A BODY of gentlemen meet now, and then to discuss this delightful subject; and at one of the recent réunions, a Mr. Martin got positively pathetic about having devoted a long and arduous life to the sewers and cesspools of his native city. Fourteen long years had he laboured to enlarge the subterranean ways and watercourses of the modern Babylon; and it is evident that he will not die happy until the filth of London is floating - at twopence a ton - over the heath of Bagshot. Mr. Martin was affected almost to tears when he talked of his exertions to carry the manure of the metropolis to the suburbs; and his ambitious desire to construct a terrace all along the banks of the Thames is a beautiful illustration of the force of the imagination, which, in the pursuit of a cherished object, forgets the existence of the wharf, the necessity for selling coals from a barge, the propriety of allowing commerce still to exist, and the vested interests of the ordinary coal-heaver. Mr. Martin would have the banks of the Thames a series of terraces, the houses palaces, and the sewers laboratories for the practice of chemistry. This is all very well in theory, but to our own eye (saying nothing of Martin) it seems rather difficult to be put in practice. "The rose by any other name would smell as sweet;" and however fine the appellation we might give to it, we fear that it will require an extraordinary zeal for science to find charms in sewers and cesspools. If Mr. Martin can only die happy on condition of carrying out his ideas about the Thames and its contents, we must of necessity predict what we should very sincerely regret-a miserable termination to his existence

Ten years after Martin's death, The Thames Embankment reconstruction work was successfully undertaken by Sir J. W. Bazalgette in three divisions the chief being the Victoria Embankment. This reaches from Blackfriars to Westminster Bridge (commenced in 1864 and finished in 1870 and costing over, a then a massive, £1.5 million). Bazalgette did acknowledge Martin's influence on his designs which are, of course, still very much evident to this day.

The famous mining engineer of this time was Thomas Sopwith F.R.S. (quoted in EXCERPTS FROM HIS DIARY OF FIFTY-SEVEN YEARS by BENJAMIN WARD RICHARDSON) who, although very unsure about William and Jonathan Martin said of their brother John:-

While pitying these two unhappy brothers, Mr. Sopwith had unbounded admiration of a third brother of the same family, the marvellous John Martin, the painter, whose works as an artist were, he thought, even surpassed by his suggestions as an engineer, by his plans for improved sanitation, and by his hopes of securing a healthy world. " Truly," my friend said, as he closed the history, " in this case it is literally the fact : — " ' Great genius is to madness close allied.'"

Further Illustrations of Martin's Schemes

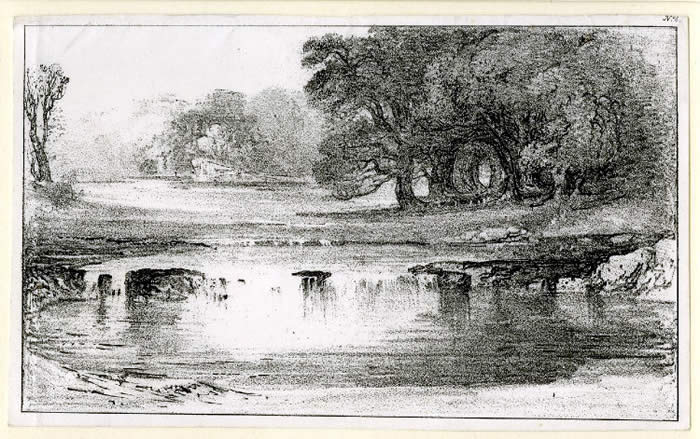

Mr Martin's Plan for Supplying with Pure Water the Cities of London and Westminster and of Materially Improving and Beautifying the Western Parts of the Metropolis (2nd Edition 1828 Page 15)

His imaginary scene of ornamental water features within Buckingham Palace grounds

Mr Martin's Sketch of a projected waterfall to the north of Kensington Gardens

Lithograph 1828 published with the second edition of 'Mr John Martin's plan ... ' as above. © Trustees of the British Museum

Martin's Proposal for a Triumphal Arch across the New Road from Portland Place to Regent's Park.

This was to be a National Monument to Commemorate Wellington's Victory at the Battle of Waterloo of 18th June 1815

John Martin also worked on a series of inventions with his eccentric brother William as the prime instigator. These involved mines, railways and ships. Following visits to William in Newcastle in 1828 and 1829, pamphlets were published Outlines of Several Inventions For Maritime and Inland Purposes

- Plan I:- Elastic Iron Ship. This proposed to make ships of iron rather than wood to secure them against shoals, rocks, tempests, artillery and fires

- Plan II:- New Principle of Steam Navigation. This featured three modifications to improve the efficiency of paddle-wheels

- Plan III:- Elastic Chain Cable

- Plan IV:- Coast Lights on a New Principle The Hilton-Jolliffe steam vessel, in which he had returned from Newcastle the previous autumn, had passed Yarmouth Roads on September 25th and Martin expected to be in sight of London the next morning. However, they had been stuck at anchor for six hours as the captain could not see the buoys marking the sandbanks. Martin proposed to fix light-towers on all dangerous shoals, twenty with blue lights between Edinburgh and the Thames and twenty two between the Thames and Dover with orange. Each would be manned by "two steady well-proven sailors"

- Plan V:- Plan for Purifying the Air and Preventing Explosion in Coal Mines*

- Plan VI & VII:- London Improvements

1837 found John promoting a paper on a laminated beam with wood and iron to the Institute of British Architects which was adopted.

* Seven years later in 1835 John appeared three times before a Select Committee on Accidents in Mines and showed his Miner's Safety Lamp modified from an earlier design by William (William's had proved better than that of Sir Humphrey Davy in tests 22 years earlier by the waste men of Willington Colliery).

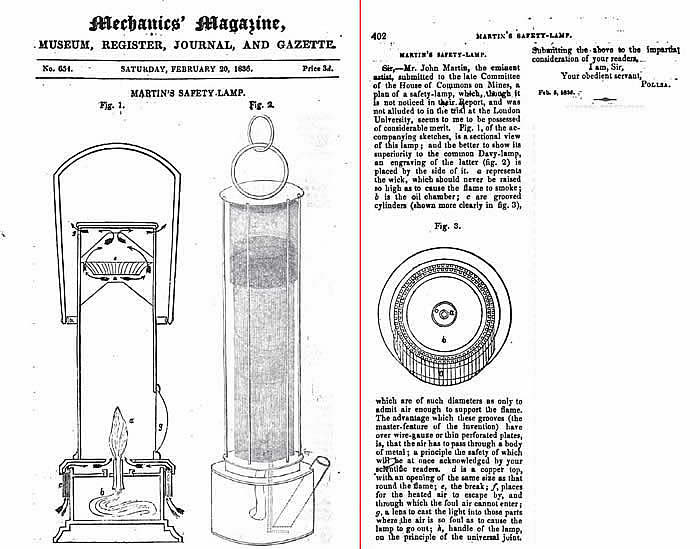

The John Martin Safety Lamp Design of 1835

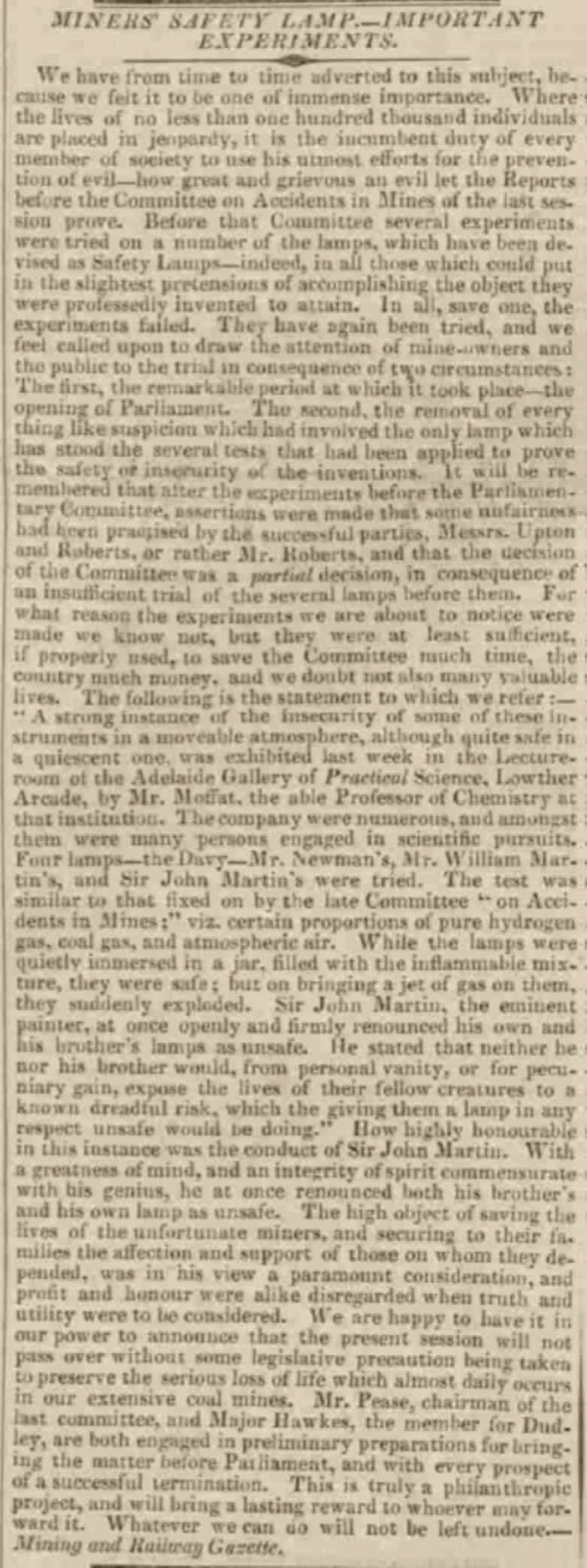

Tests on various safety lamps were conducted by a Mr Moffat in February 1837 using a 'moveable atmosphere' These demonstrated the insecurity of both variants of the Martin's lamps. John Martin was present at the tests and immediately accepted that neither his nor William's was safe.

A report as published in the Mining and Railway Gazette printed in the Newcastle Journal 18th February 1837 is below.

(I am very grateful to Mr Dave Rimmer, who has extensively researched mines safety lamps, for providing this information)

Finally in 1849 the Mines Ventilation ideas were deemed a positive answer to mine safety and Davy admitted his lamp was of limited use too. Credit was given to brother William Martin who had suggested this many years before.